Raising Resistance Fighters

Parents have the power to buck the tech undertow. We just have to use it.

Author’s note: As the new school year kicks into high gear, I wanted to share this essay adapted from a keynote address I delivered a few years ago at a back-to-school parenting conference in San Diego, CA. The challenges of parenting in our Age of Distraction have only escalated since then, so I’ve added some new studies and reflections on the costs of tech overload and the choice we always have, by God’s grace, to break free. ~ CCC

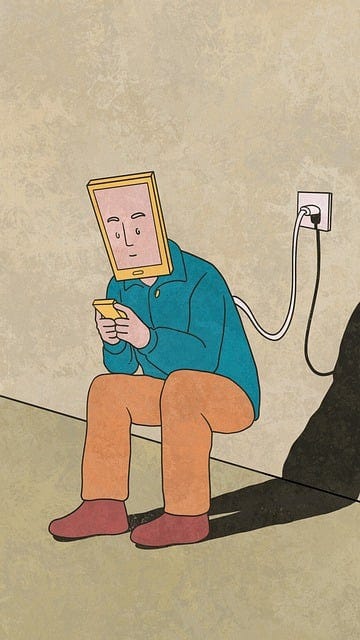

In 1936, when color televisions had yet to be invented and FM radio was still a novelty, poet T.S. Eliot famously described his contemporaries as “distracted from distraction by distraction.” Eighty-eight years and 2.3 billion iPhones later, his words ring truer than ever. Our gadgets and apps keep accumulating; our collective attention span keeps shrinking; and we are raising the first generation born into a hyper-connected, screen-saturated digital world.

Members of this “Generation Alpha,” as it’s been dubbed, are guinea pigs in a vast social experiment. We don’t yet know how it will turn out, but the early returns aren’t promising. Researchers have linked heavy screen use in children to everything from sleep deprivation, impulsiveness, nearsightedness, behavior problems, and reading, language, and social delays to sedentary lifestyles and obesity, higher rates of ADHD, IQ deficits, anxiety, and even—in the case of excessive social media use—a higher risk of suicide.

A laundry list like that tends to make the eyes glaze over. But drill a little deeper into those studies and the human costs of weaning kids on screens come into painfully sharp focus.

Consider the national data on screen use and depression analyzed by psychologist and iGen author Jean Twenge. She found that eighth graders who are heavy social media users increase their risk of depression by twenty-seven percent, while teens who are heavy social media users are thirty-five percent more likely to have a risk factor for suicide, such as having a suicide plan. It seems that today’s teens are spending more time alone on phones than with friends, which may explain why teen homicides are down while teen suicides are soaring. All those hours spent scrolling social media—watching friends have fun without them, comparing their lives to airbrushed versions of the lives of others, connecting with cyberbullies and online predators who can target them 24/7—isn’t healthy for an age cohort known for roller-coaster emotions and poor impulse control. Summing up the data on what she labeled “the worst mental-health crisis in decades,” Twenge said this in a 2017 article for The Atlantic:

Teens who spend more time than average on [screens] are more likely to be unhappy, and those who spend more time [than average] on non-screen activities are more likely to be happy. There’s not a single exception. All screen activities are linked to less happiness, and all non-screen activities are linked to more happiness.

That might not be such bad news if most kids were moderate tech users, but according to the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, the average eight-to-twelve-year-old spends four to six hours on screens a day, and the average teen spends up to nine. That’s a far cry from the two-hour daily max recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics. It’s also an astounding chunk of their young lives, the equivalent of almost twenty weeks—or nearly forty percent—of every year spent staring at screens. Don’t imagine that’s happening only after school: A Common Sense Media study released last year found that ninety-seven percent of teens use their phones at school, mostly to check social media or play games, and they receive an average of 237 phone notifications per day, a quarter of which arrive during school hours.

Kids themselves often know something is out of whack. A Pew Research Center study released this year found that four in ten teens say they spend too much time on their phones, and that Common Sense Media survey found more than two-thirds of teens admitting they struggle to cut back on their technology use, use technology to escape tough feelings, and miss sleep due to being online late at night. They see the same problems in their parents: Nearly half of teens in the Pew study said their parents are sometimes distracted by their phones when their teens are trying to talk to them—a far higher, and likely more realistic, percentage than the thirty-one percent of parents who admitted this happens regularly.

Digital crack for kids

All of which brings us to the issue of attention, and specifically, the question of how we can harness the power of attention to make our parenting journey more rewarding and our children more focused and free.

Neither are tasks for which we’ll get much help from our popular culture. Harvesting our attention is a multi-billion-dollar business, and hooking our children and us on new technologies and digital content is priority number one. That intense tug we feel toward our devices—and see our children feel toward theirs—isn’t a bug of our attention economy. It’s a feature.

Today’s digital products are designed to keep us looking even when we shouldn’t and to make it difficult—and for a child with a still-developing brain, well-nigh impossible—to look away. As Sean Parker, founding president of Facebook, once confessed: “The thought process [behind Facebook] was: ‘How do we consume as much of your time and conscious attention as possible?’” The answer, he said, was to “exploit a vulnerability in human psychology”—our brain’s craving for pleasure. Which is how we wound up with digital technologies that Big Tech insider Chris Anderson famously compared to illicit drugs. “On the scale between candy and crack cocaine,” Anderson told The New York Times, “[these technologies] are closer to crack cocaine.”

The analogy may be more apt than you think. The same transmitters in the brain that reward the cocaine user with short-term feelings of intense pleasure and cravings for more are activated in our brains when we use smartphones and other tech devices that offer instant responses. The dopamine hits delivered by smartphone use aren’t nearly as intense, of course—phone users don’t feel a physical high—but the chemical reaction is real. This “dopamine-driven feedback loop” helps explain why we find it so hard to put down our phones or get kids to put down theirs.

It also explains the emotional low that follows screen binges. In a landmark 2018 study, University of Pennsylvania researchers monitored the phone data and social media use of 143 college students and found a causal link, not just a correlation, between social media use and depression. The more minutes students spent on social media, the lonelier and sadder they felt. The inverse was also true: Less time online led to more happiness and belonging. The lead researcher summarized the study’s upshot in stark terms: “Put your phone down and be with the people in your life.”

Ignoring that advice won’t just make kids sadder. It may make them less mentally sharp. A National Institutes of Health study recently found that nine- and ten-year-old children who spend more than seven hours a day on screens are more likely to experience premature thinning of their brain’s cortex, the outermost layer of the brain that plays a key role in critical thinking, memory, language, action, and attention. Scientists aren’t yet sure what this means—some thinning of the cortex is normal for kids—but some doctors are already sounding the alarm over “digital dementia”: a breakdown in focus and memory in children and teens who spend too much time on screens. It seems that the MRI scans of these kids look disturbingly similar to those of adults with Alzheimer’s or brain injuries. And a roundup of research studies recently published by The International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction noted links between heavy screen use in kids and learning delays, mental health problems and addiction, and a higher risk of early onset dementia in adulthood.

There’s a reason all those Silicon Valley software engineers who design our apps and games and gadgets won’t let their own children use them. Or that they wax eloquent about the educational benefits of technology in public schools while sending their own kids to Waldorf schools where screens are banned. Or that the digital divide between rich and poor now is less about access to technology than limits on it, with lower-income children far more likely to spend their free time online while the children of tech titans like Steve Jobs and Bill Gates are raised screen-free.

The new brain drain

None of this is to say that today’s technologies don’t offer us benefits: the ability to work from home; to stay in touch with loved ones around the clock and around the world; to have a world of information at our fingertips. Screen time clearly can be well-spent.

But we should never forget that these technologies exist first and foremost to turn a profit. The social networks, apps, and games that we love hook our attention and gather our data to resell it to advertisers. We may use them for free, but in an attention economy, if you’re not paying for the product, you are the product. And our children have become products par excellence: little proto-consumers whose attention spans are being bought and sold and brains being rewired in ways we only dimly understand.

What we do know for certain is that today’s interruption technologies have put us all in the habit of what Apple insider Linda Stone calls “continuous partial attention”—a state of mind in which our focus is always divided. We like to think we’re multitasking, but research suggests our brains in this state are actually more like outmoded desktops switching between open windows. When we’re paying attention to one, we’re not really attending to the others, and all those open windows slow our processing time.

That’s true even of kids who seem to be seasoned tech multitaskers—doing homework with ear buds in, writing school papers with one eye on social media feeds, powering through a textbook with the TV blaring. We want to believe they learn differently than we did, but the research suggests they’re just learning less. A 2006 UCLA study found that we use different parts of our brains when trying to learn something while multitasking versus when we’re paying full attention. And the part of the brain we use while multitasking doesn’t equip us as well as to recall the information later or put it to use in flexible, abstract ways—the ways needed for college-level or professional work. So unless your kid plans to skip college and work an assembly line, doing his schoolwork while consuming several other sources of media is not giving him the preparation he needs to succeed.

It may also be making him more distractible—even after his devices are powered down. A 2009 Stanford study found that students who are heavy media multitaskers perform worse than focused learners on everything from paying attention to controlling their memory to switching between tasks. That poor performance wasn’t logged while they were multitasking, mind you: It happened when the screens were off and kids were trying to concentrate. Researchers concluded that the pathways in their young brains had been rewired by digital technologies and had become more vulnerable to distraction.

Sometimes the mere presence of a smartphone within arm’s reach is enough to make learning difficult. A 2017 study published by the University of Chicago Press found that college students who silenced their phones and left them face down on their desks or in their bags did worse on cognitive tests than those who left the phones in another room. That disadvantage held true even for students who weren’t consciously thinking about their phones but simply had them nearby. Smartphones, the researchers concluded, are creating a new kind of generational “brain drain.”

Parent, discipline thyself

Here’s the good news about today’s tech undertow: We don’t have to surrender to it. We can choose what works for us and for our families rather than blindly following the crowd. As parents, we are the number one influence in our children’s lives—an even stronger one than friends, the experts say, no matter how loathe the average teen may be to admit it. So raising kids who are focused and free is still possible, even in this culture, if we’re willing to reclaim our parental power and discipline ourselves as much as we discipline our kids.

That’s the tough part, of course. Not simply to set tech limits on our kids but to limit ourselves. The same digital disruptions and social pressures that scatter their focus scatter ours, too. That’s the very definition of distraction, after all: The word comes from the Latin roots “dis”— which means away or apart—and “trahere”—which means to drag or pull. To be distracted is to allow our focus to be dragged away, to let our peace be pulled apart and scattered.

It’s a common temptation. I’ve succumbed myself, more times than I care to admit. It usually happens on a homeschool morning that begins extra bumpy. You know the kind: You wake up tired; the kids are cranky or sick or too loud; the weekend feels light years away and material they mastered only days ago seems like a foreign language to them now. You tell yourself no one will notice if you sneak a peek at your phone.

Then you sneak another. And another. Maybe you scroll the headlines or social media, reply to that email that could have waited, fire off a text to a friend that starts a conversation you suddenly can’t ignore. You tell yourself you’re keeping up with current events, making important connections, giving yourself a well-deserved break. But next thing you know, a half-hour has passed, then an hour. You’re behind on school; the kids are off-task; and you’ve fallen down the Internet rabbit hole. You have a million things on your mind, none of them related to what you actually need to be doing in this moment. And the rest of the day feels scattered and rushed and altogether too much. You find yourself groaning as you check the time, wondering why homeschooling is so hard and if the day will ever end.

Maybe you never have mornings like that. If so, congratulations. We’re all jealous.

For the rest of us ordinary mortals, it’s a struggle to stay off our phones and pay attention to the flesh-and-blood people around us when the blue light of the screen beckons.

It helps to remember that little eyes are watching, that kids notice our “presentee” parenting—our tendency to be present in body but not mind when smartphones are out—and they resent it. In her study of several thousand kids, parents, and teachers for her 2013 book, The Big Disconnect, Harvard psychologist Catherine Steiner-Adair found that children of all ages used the same types of words when discussing how it felt to try to get the attention of a tech-distracted parent: sad, angry, mad, frustrated. It’s like sibling rivalry, she concluded, only today’s kids play second fiddle to a device, not a person.

Parental tech distraction leads to more than hurt feelings. In August, a team of researchers led by University of Calgary psychologist Sheri Madigan published a study in JAMA Network Open that found higher levels of “parental technoference”—parents interrupting interactions with children to attend to phones or other devices—were linked to higher levels of anxiety, hyperactivity, and inattention in kids. Similar studies have found that infants react with distress when their present-but-not-attentive mothers stare at phones instead of them; that parents are more likely to discipline in overly punitive ways when absorbed in their smartphones; and that parents who use their phones more often around their kids tend to have kids with higher rates of behavior problems. Those kids might also have more broken bones: The CDC recorded a ten percent uptick in the rate of unintentional injuries to children in the first five years after the iPhone debuted in 2007, something widely attributed to more tech-distracted parents at the playground.

Most of us know we need to put down the phones and pay attention to people, especially little people. Yet too often, we don’t act on what we know—at least, I know I don’t always act on it. Instead, I drift through some days, letting distraction get the best of me, then wondering why I feel grumpy and dissatisfied and vaguely guilty at the day’s end, as if I let something precious slip away, something I may never get back.

The truth is, I won’t get these parenting and homeschooling days back—any of them. The time to enjoy my children, to give them my undivided attention, to treat them as if they are the most important thing in the world to me, because they are: That time is now.

I don’t have to be perfect. But I do have to be present, truly present, if I want these years to be ones I remember with fondness rather than regret. Because someday soon, I’ll find myself with a quieter home and shorter to-do list, with children grown and gone away their own adventures, no longer so hungry for my attention. This journey of raising kids, like all journeys, will come to an end. And I’ll be left with more solitude and silence than I might want to reflect on how I spent these days that melted into years.

“How we spend our days,” says author Annie Dillard, “ is … how we spend our lives. What we do with this hour, and that one, is what we are doing.”

I don’t know about you, but I don’t want to look up at the end of my parenting journey and realize that what I was doing … was looking at my phone.

Love and limits

So if attention, like distraction, is a habit, how do we get into it?

We can start by eliminating obvious temptations. If having a smartphone in sight erodes our will to focus just as having a piece of chocolate cake on the counter drains our determination to diet, we should put away the smartphone like we’d put away the cake. And let’s not tell ourselves any lies about digital calories that don’t count: A UC Irvine study found that it takes roughly twenty-five minutes for our brains to get back on task after we give in to one digital distraction. So that thirty-second peek at Twitter actually costs you nearly thirty minutes of attention.

With that in mind, decide how often you’ll check your phone, especially during homeschool days or family times: Once an hour? Once in the morning and once in the afternoon? Make a realistic plan and stick to it, then tell friends and family so they can expect slower responses during those times. And remember that your kids are watching—for homeschoolers like me, the kids are always watching—so cheating on our resolutions is cheating them of the chance to see self-discipline in action.

We can also turn off notifications on our phones—all of them. This won’t work for every profession or circumstance, but it’s remarkable how much focus you can gain with this little hack. I did it a few years ago, first with emails, then texts, and was amazed how much time and attention I recovered. Sometimes I also turn off email accounts on my phone, so my phone ringer is the only thing on during the homeschool day. I can still check for texts and emails—and I still check more than I should—but it takes more time and trouble. I’m forced to stop and think before I take that sip of distraction: Is this really the best way to spend these moments? And what am I looking for, anyway?

We can set similar limits for our kids, and we’ll get far less flack if they see us practicing what we preach. How many hours a day do you think your kid should spend on a phone or tablet or playing video games? Set a number and hold firm. Do the same with TV and movies. If you’re going to watch TV, do so intentionally. Some families decide in advance what shows they’ll watch and when the TV will turn off, so a blaring boob tube doesn’t become the electronic wallpaper of family life. Others keep TVs out of bedrooms or move their main screen to a less prominent place in the home so it’s not the focal point. Still others observe a “screen sabbath” when everyone in the family—mom and dad included—must power off all devices and go one full day together without screens.

In our family, kids don’t have smartphones and there’s no TV—hasn’t been ever since shortly after our oldest children were born, back when I was still hosting my own national television shows and appearing regularly on cable news networks. (You can read a little more about how and why my tech habits changed in my latest book, The Heart of Perfection.) Maybe you’d say that’s too extreme; I have plenty of friends and relatives who’d agree. My point is simply that strict limits are doable. If you’re determined to live an intentionally low-tech life, and willing to risk looking a little weird in the process, anything is possible.

Beware making the perfect the enemy of the good, though. If even the lesser limits mentioned above seem too intense, start smaller: with one hour less screen time per day per kid or no phones at family meals or no screen use within an hour of bedtime or inside the bedroom, so blue light and cyber-bullying can’t steal your kid’s sleep. If there’s one point all the experts agree on when it comes to kids and tech, it’s that some limits—any limits—are better than none.

Digital detox may be painful for your kids, but don’t let that rattle you. Kids are adaptable, and the same neuroplasticity that makes too much screen time harmful for them also enables them to replace bad habits with better ones. Being the last one to give your kid a smartphone or the first to turn off the tablet or TV on weeknights won’t make you the cool parent, but it may make you the one your kids thank someday when they realize you put their welfare above your desire to keep the peace.

‘The education par excellence’

Will we raise perfectly focused kids or achieve perfect focus ourselves? Of course not. Wandering attention and vulnerability to sensory stimuli are built-in features of our humanity; neuroscientists say they helped our hunter-gatherer ancestors find food and dodge predators.

Still, we don’t have to be hapless victims of biology or technology. We can learn, even from a young age, to focus on what we want more than what we don’t, to pay less attention to what we’re giving up than what we’re aiming for.

In the big picture, what we’re aiming for is the education and formation of children who are joyful and alive to the world around them; whose eyes are bright with curiosity, not stupefied with a screen-fixed stare; children who brim with wonder and gratitude and imagination; who ask endless questions as they explore the marvels of nature and the paradoxes of history; who appreciate the beauty of sunsets and sonatas, mathematical equations and Olympic equestrians; who can stand a little silence and stillness even as they relish action and adventure; children who grow into adults that know the freedom of focusing on what they value, rather than being led around by the nose by Big Tech programmers and profiteering online influencers.

If we keep our eye on that prize—the prize of joyful, purposeful, peaceful children who think critically and live intentionally—cultivating the habit of attention becomes more a challenge than a chore. We start to see attention as less about navel-gazing than star-gazing. It’s about looking in the direction of what we want most, stretching toward our deepest desires. That’s what the Latin roots of the words attention and desire mean, in fact: Attention comes from “ad” and “tendere,” which means “to stretch toward,” while desire comes from “de” and “sidus,” which means “from the stars.” Attention is a stretching toward what we desire, toward what is above.

Stretching entails struggle. It’s more like a marathon than a day at the spa. But the struggle is itself a valuable experience—for us, and our kids. You learn to pay attention by struggling to pay attention, even—especially—when what you’re attending to isn’t immediately interesting. And it doesn’t take much to strengthen our attentional muscles. In their book, The Distracted Mind, neuroscientist Adam Gazzaley and psychologist Larry Rosen argue that the mere practice of delaying your next peek at a screen, and gradually increasing the length of time you go between smartphone checks, can retrain your brain to focus.

That’s a valuable skill, arguably one of the most valuable we can teach our children. In a culture of disruption technologies constantly drawing eyeballs in every direction, the future belongs to those rare, disciplined souls who can command and direct their own attention. As William James once put it, “the faculty of voluntarily bringing back a wandering attention, over and over again, is the very root of judgment, character, and will. … An education which should improve this faculty would be the education par excellence.”

Let the resistance begin

Much of this is common sense. But common sense is too often forgotten in our tech-dazzled times, when every new Apple gadget is greeted as the Second Coming and questioning the dominance of screens is regarded as reactionary.

We don’t have to drink that Kool Aid. We can take a stand, however hidden, for greater freedom from distraction for our ourselves and our kids. We can become what media theorist Neil Postman labeled “loving resistance fighters” in a world of distracted technophiles, rebels who refuse to kneel at the altar of each new tech trend and who operate by a higher parenting principle than “everybody’s doing it.”

Resistance fighters aren’t Luddites; they don’t hate technology or reject trends just to be different. They ask questions and set boundaries. As parents, resistance fighters draw a line in the sand when it comes to technology’s influence on their children. They say: You may come this far and no farther. They hold that line even when everyone else is giving in, and play the long game out of love. Then they step back and watch their children grow up free from the shackles of incessant distraction, free to cultivate the focus and vision and discipline to change our world for the better.

“Attention,” philosopher Simone Weil once said, “is the rarest and purest form of generosity.” This school year, let’s give our children that rare treasure—the gift of our attention, and the chance to harness and direct their own attention to what matters most.

Brilliant Colleen. I couldn't agree more with everything you wrote. Like Dr. John Delony from the Ramsey Network once said about his and a close friend of his in regards to their shared family policies on no tech for their kids, "We're gonna be the only ones. We're gonna be the only ones. And that's okay."

Know that you're not the only one out there who is working towards raising kids well without having them fall into the bottomless abyss of the Mines of Moria tech pit. Thank-you for these well curated thoughts and all your thorough research.

Vive la Résistance!